Miscellaneous

Tonga Chronicle

The King and I

Taufa‘ahau Tupou IV was a king-sized king. The ruler of the island nation of Tonga stood 6 ft. 5 in. and tipped the scales at 400-plus pounds. His size was such that he required special chairs to support his weight.

I know, because I interviewed His Majesty on the patio of the royal residence, a red and white gingerbread pālasi in Nuku’alofa, Tonga’s capital. It took both hands and all the strength of my scrawny 135 pounds to pull up a matching armchair.

The year was 1969. I was a twenty-something Peace Corps volunteer, fresh out of Northwestern University Medill School of Journalism. I had joined the Peace Corps hoping to be assigned to South or Central America and to become fluent in Spanish.

The Peace Corps had a different idea. Instead of South America, it sent me to the South Pacific. It was expanding to Polynesia. The king of Tonga had requested teachers, health aides, and a few specialists in agriculture, marine biology, tourism, and journalism.

I was to be the journalist.

Tonga is an archipelago of about 170 islands. The official language, Tongan, is unique to its 100,000+ inhabitants, double if you add the Tongan diaspora.

Malo e lelei, Lisiate! Hello, Richard!

No se habla español.

Tonga was a British-protected state on the cusp of becoming fully independent. Its sole newspaper was the state-owned Tonga Chronicle, published simultaneously in English—the primary language in government and business circles—and Tongan, the Kalonikali Tonga.

My task was to help the weekly paper raise its standards of reporting.

A Western journalist assisting a government-owned newspaper in a Polynesian monarchy? I’m not sure that’s what John F. Kennedy had in mind when he conceived the Peace Corps to provide grassroots assistance and promote peace and friendship.

It was uncharted territory. But everything about “Tonga 1,” the inaugural group of volunteers, was groundbreaking. In the absence of U.S. foreign aid—Australia and New Zealand were key to economic development in the region—the Peace Corps was the face of America.

Volunteers underwent months of immersive training to learn Tongan and to prepare for two years of cold showers, Coleman lanterns, and kerosene stoves. The Peace Corps gave us a $25 monthly stipend, six chickens, and seeds for a vegetable garden.

The position was called “volunteer” for good reason.

As the group’s journalist, I walked a tightrope. Tonga was a constitutional monarchy with a complicated and rich royal history. It was a semi-feudal society. Hereditary nobles had outsized roles. Cravings for fuller, representative democracy would play out decades later.

My title at the Chronicle was “advisor.” The advice I gave myself: Steer clear of politics. Let my colleagues handle government pronouncements. Stick to bread and butter concerns.

In Tonga, bread and butter were coconuts and bananas.

The romantic image of the South Pacific is coconut palms and banana plants swaying in the tropical breeze. But when that breeze becomes a hurricane or cyclone, romance can turn to ruin.

Bananas bruise. Coconuts shake loose. Trees are uprooted.

EXTRA! EXTRA! READ ALL ABOUT IT! Black Leaf Disease! Bunchy-Top Virus! Rhinoceros Beetles!

Palm Rats!

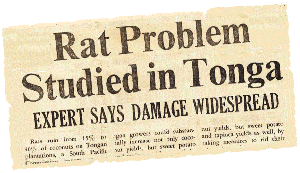

Discolored fruit, vermin and pests make for front page news. Tropical insects feed on the sap of rotting trees.

Rodents nest in the fallen leaves.

“Rats ruin from 15% to 40% of coconuts in Tongan plantations,” the Chronicle explained. Land owners and leaseholders were urged to search and destroy breeding sites.

Tonga’s economy relied upon agriculture, fishing, and money sent home from Tongans living abroad. The kingdom had no mineral resources to fall back on.

Or did it?

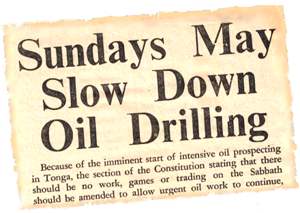

Could you imagine the headlines if, say, oil lie hidden beneath the volcanic bedrock and coral limestone?

You don’t have to imagine.

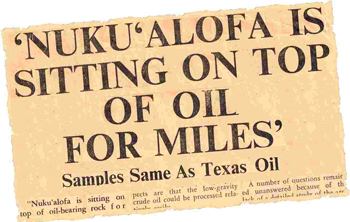

STOP THE PRESSES! “Nuku’alofa is sitting on top of oil-bearing rock for miles,” the Chronicle heralded the news.

A shallow seepage was discovered under swampy mangrove mud in porous limestone near the capital’s coastline. The viscous substance had the look and smell of petroleum.

Samples were rushed to the Geological Survey Department in neighboring Fiji for chemical analysis.

Yes? No?

The answer from the experts was unambiguous: “This is the real McCoy. It’s live oil . . . exactly the same oil that has been mined in Medina, Texas.”

Medina was known for a low-gravity crude that can be easily processed.

Prospectors, start your engines!

Tonga’s Public Works Dept. rolled out tractors with excavators.

Townsfolk went at it with shovels and garden hoes.

Churchgoers used crowbars.

New seepages were discovered on a private allotment in the area of Fasi.

Another was found at an agricultural cooperative in the village of Lifuka.

Pray tell, a seepage was discovered on the grounds of a Wesleyan church.

“It’s as thick as tar seal,” the church’s minister exclaimed.

The church was three blocks from the royal palace. Thy kingdom come, thy oil be done.

Suddenly, black gold was everywhere.

In the village of Kolomotu’a, a filmy substance was discovered on the reef’s edge of the waterfront.

In Kolofo’ou, small globules surfaced at the deep-water wharf.

On the island of ‘Eua, oil bubbled up in boat harbors.

Discoveries were reported in towns and islands whose names had more vowels and glottal stops than residents. Places like Niuatoputapu, north of Vava’u.

Try saying Niuatoputapu three times fast.

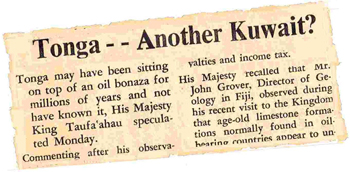

“Tonga may have been sitting on an oil bonanza for millions of years and not have known it,” the king enthused.

Rich monarch, poor monarch. His Majesty will take rich.

How rich?

“Tonga—Another Kuwait?” the Chronicle asked. We reported that the State of Kuwait earned $4 million a day pumping oil.

If an emirate in the Persian Gulf could strike it rich, why not a kingdom in the South Pacific?

Tonga was about to gain full independence from Britain. It would become the newest member of the Commonwealth of Nations.

Nothing says common and wealth more than oil.

Britain dispatched a London-based petroleum consultant.

Fiji offered up its senior geologists.

New Zealand deployed a seismic vessel for ocean survey.

Royal Dutch Shell/Australia came calling . . . then British Petroleum . . . and Mobil Oil and Republic Mineral Corp. from the US . . . and Canadian Superior Oil . . . and French Pétroles d'Aquitaine.

Everyone wanted a piece of the petrol.

Tonga’s Legislative Assembly took action. It passed mining regulations and formulated royalties.

It revised tax laws and drafted lease agreements.

After prayerful consideration, it loosened Tonga’s Sabbath laws.

It had been illegal to swim, play loud music, or conduct business on Sundays. Parliament amended the Constitution to allow oil operations 24/7.

Drill, baby, drill!

Spoiler alert: Oil exploration is highly-speculative. The failure rate is high.

It’s one thing to strike a pocket of oil. It’s another to tap large accumulations.

Royal Dutch Shell got the green light to drill exploration wells. It found oil and gas trapped below Tonga’s subsurface in close proximity to seepages.

Commercial potential?

Crude, but no cigar.

Enter British Petroleum. BP found traces of seabed minerals. But the same verdict: Not marketable.

The numbers are the numbers. Thanks, but no thanks.

The other majors, ditto. Pockets of genuine crude, but no deep reserves.

Oil exploration is complicated. It's a long process. It consumes decades.

When King Tupou IV passed away in 2006 at age 88, his legacy did not include sunken riches.

Last I checked—two kings later—Tonga was not on the list of oil-producing nations.

In October 2017, the Peace Corps marked the 50th anniversary of Tonga 1. The volunteers for Tonga #83 set foot in a nation still reliant on coconuts, bananas, fishing, and remittances from expatriate Tongans.

The group of 25 included teachers to help with English literacy in primary and secondary schools. There was no journalist among them.

Sad to report, there also was no newspaper.

The state-owned Chronicle had ceased publication in 2011 after a brief go at privatization. Like oil exploration, the failure rate of newspapers is high.

Had the Chronicle survived to 2018, the big story would have been Cyclone Gita, a storm packing winds of 121 mph. Gita flattened parts of the Parliament House, smashed churches, toppled electricity lines, leveled fruit trees, and flooded streets and property.

Thousands were left homeless. There were two confirmed deaths.

If you’re looking for a silver lining, there were no oil tankers to contaminate wetlands or marine life.

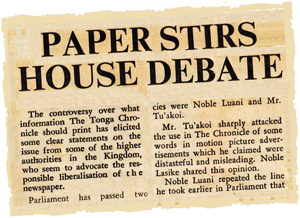

One of the lessons from my Chronicle residency was that oil and newspapers do not mix. That visit to the palace in 1969? It was to quell an uproar over the role of the press in a monarchy.

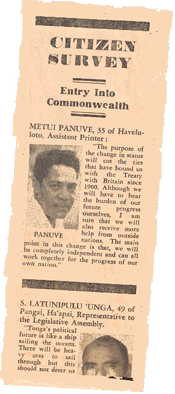

The Chronicle had come under attack in Parliament for introducing a Q&A column that gave voice to the newspaper’s readers.  The legislative assembly was comprised of People’s and Nobles’ representatives. One of the Nobles objected to the “outspokenness” of commoners.

The legislative assembly was comprised of People’s and Nobles’ representatives. One of the Nobles objected to the “outspokenness” of commoners.

Citizen Survey was modeled after the iconic Inquiring Photographer, a New York Daily News feature that posed existential questions, e.g., “Does New York have too many dogs?”

The Chronicle knew better than to inquire about the canine population in Tonga, where some consider dogs haute cuisine. But we did address the appetite for oil.

The consensus: Bring on the oil rigs. One of the petrol enthusiasts was a gas station attendant who urged Parliament to put pedal to the metal.

In hindsight, we should have put the brakes on oil and asked about dogs.

“Who started the Citizen Survey?” the Noble’s Representative wanted to know. “Why should the people speak their minds?

“They should stay where they are,” he said.

A People’s Representative took exception. “This country is a democracy,” he responded.

”The Constitution protects speech,” he said.

For the record, Section VII of Tonga’s Constitution states “it shall be lawful for all people to speak, write, and print their opinions . . . there shall be freedom of speech and of the press forever.”

If you read a little further, it also states that “nothing in this clause shall be held to outweigh the law of slander or the laws for the protection of the King and the Royal Family.”

Welcome to a constitutional monarchy.

Unstoppable force (constitution) meets immovable object (monarch).

What sayeth the monarch?

King Tupou IV welcomed me to the palace. After offering an honorific greeting and grappling with the heavy armchair, I pressed Play–Record on my tape recorder and began asking questions:

What is your interpretation of the constitutional guarantees regarding the press? Is Tonga different from other countries with similar press laws? What place should opinion, such as a Citizen Survey column, have? What are your attitudes towards a private newspaper in Tonga? How do you regard Parliament criticisms of the newspaper?

King Tupou IV was a learned man. He studied arts and law at Sydney University. One might say he was a philosopher king.

His attitude was: Give a little, take a little.

Giveth: The aim of the Chronicle should be the same as any other newspaper—disseminate responsibly-gathered information. Newspapers are a check on government. Officials can benefit from public opinion. They should develop a thick hide.

Citizen Survey? Not a problem.

Chalk up Round 1 for Feedom of the Press.

Taketh: This is Tonga. Tongans lack the experience of a free press. The government finances the newspaper. That makes some officials nervous. Development should be gradual and careful.

Score Round 2 for feudalism and gradualism.

King Solomon had nothing on King Tupou IV.

The Chronicle ran with the full interview. Citizen Survey lived to see another day.

It wasn't the final chapter, however. Decades later, attempts to stifle dissent would escalate as the publishing landscape broadened.

An independent paper, Times of Tonga (Taimi ‘o Tonga), locked horns with the establishment. It led to arrests, court battles, and stricter laws regulating the media.

One step forward, two steps backward.

Taufa‘ahau Tupou IV's reign was a balancing act. He was a Western-educated king presiding over an aristocratic system of government.

He championed education. He was instrumental in making Tongans the most literate people in the region. He built many primary and secondary schools. He established the kingdom's first teacher training college. He welcomed the Peace Corps.

That said, he was the custodian of a monarchy whose royal lines date back to 1845. Tonga is the last of the Polynesian kingdoms. The king was the embodiment of their rich culture. Tongans revere tradition.

But some of the reverence turned to unrest with the dawn of a new century. Tonga languished in poverty while the royals profited from state assets and business interests.

The last years of the king’s 41-year rule were mired in controversy, including ministerial extravagances and a quick-money scheme to sell passports to foreigners. Ordinary Tongans—the beneficiaries of modern education—sought changes.

Shortly after his death in 2006, rioters decimated central Nuku‘alofa when reforms stalled. They ransacked government property and burned businesses.

Tupou IV's heir to the throne, Siaosi Tupou V (Crown Prince Siaosi Taufa'ahau Manumataongo Tuku'aho Tupou), saw the palace walls closing in. He relinquished many of his powers. The royal family began divesting itself of business holdings.

It was a prelude to new elections. For the first time, a majority of the Parliament would be elected by popular vote.

Today, Tonga remains a constitutional monarchy. More democratic? Less monarchial?

The right balance?

That's a question for a Citizen Survey.

INTERVIEW

Future of the Press

The following is my interview in 1969 with King Taufa'ahau Tupou IV on the future of journalism in the Kingdom of Tonga and the role of the national newspaper, the Tonga Chronicle. Prior to the newspaper’s establishment in 1964, the only regularly-printed news publications were a government gazette, a daily sheet published by the Premier’s Office, and several church bulletins. The Chronicle ceased publication in 2011 after a failed consolidation with privately-owned Times of Tonga.

Prior to the newspaper’s establishment in 1964, the only regularly-printed news publications were a government gazette, a daily sheet published by the Premier’s Office, and several church bulletins. The Chronicle ceased publication in 2011 after a failed consolidation with privately-owned Times of Tonga.

Q.: What directions do you think the newspaper should be taking?

A. (King Tupou IV): “I think the first aim of a Tongan newspaper should be the same as any other newspaper situation: to disseminate responsibly-gathered and written information. And the first duty of a newspaper is public information. The directions of a newspaper should be governed first and foremost by this objective.

I think this question of public information is particularly important where the newspaper is the only newspaper in any particular place, such as Tonga. Where, of course, there is a multiplicity of newspapers, then, whereas you might be able to influence one, you can’t influence them all, and they will always be able to say what they think about any given issue.

But where the newspaper is the only newspaper, and admittedly because this newspaper is being financed by the Tongan government, from time-to-time employees of the Tongan government or officials in it may be nervous owing to that connection, and think that what is said by The Chronicle may be misinterpreted to be the views or attitudes of the Tongan government itself. Such nervousness is understandable. These views are only held because they are not used to newspapers making comments on public affairs.

I should say, had they experience in a country where a free press is the rule rather than the exception, they’d find governments in that country tend to develop a hide about as thick as a rhinoceros hide, and newspaper, radio and television criticism simply bounces off.

This attitude has not yet developed in Tonga. But I think it will come about in due course. I think this debate about the Citizen Survey shows that there are members of parliament who value some of these comments by members of the public. In any case, I don’t think myself that criticism is necessarily bad. If there’s truth in it, of course, the people who are being criticized can only benefit from it. Criticism that is false should be replied to, and the truth made known.

Q.: What is your interpretation of the constitutional guarantees regarding the press?

A.: I think it means what it says.

Q.: Is Tonga very much different from other countries with similar press laws?

A.: I don’t think so. The only thing, of course, is that one has to realize that The Chronicle is probably the third newspaper in Tongan history; there have been one or two newspapers before. And all of the chief newspapers that have ever been published in Tonga have been government newspapers, with the very exception of one or two newspapers operated by various religious denominations. And, in fact, Tonga has had no experience of a free press such as is usual in other countries. I think if you take this historical circumstance into account, freedom of the press will have to come gradually and carefully; it shouldn’t be too much of a shock so that the system can’t stand it.

Q.: Is it government’s wish that the paper expand or otherwise broaden itself? If so, in what ways?

A.: I, myself, would like to see a bigger, better Chronicle, because I think people are very short of reading matter, and they are very short of reading matter that comments or gives them news of things that are really of public importance. Whereas now, The Chronicle can only do straight news stories, something may be gained if it can do feature articles on certain things, and do a little more research in depth about the problems in Tonga.

Provided we can staff the paper properly, The Chronicle, being a weekly publication, will be in a better position to do this than a daily that has to keep meeting a deadline all the time.

Q.: What place should opinion, such as a Citizen Survey column, letters to the editor, or opinion columns, have in The Chronicle?

A.: I think this is a development that should be encouraged. Many of the things they express opinions on are questions of public interest, and it is always valuable for public services or businesses or whatever other groups are carrying on to know their public image and any shortcomings there may be in the services or activities they carry out.

I think it is quite harmless, and in some cases can be extremely useful. Abroad, there are institutions that are constantly taking public opinion polls on political questions, or customs, or preferences for commercial articles. All of that is an attempt to understand what people think, because what people think is of great importance. It decides matters for them, which measures their support or lack of support, what things they lack, what things they don’t lack. All of this can provide a useful guide.

Some of the biggest mistakes in the world have been made by people who have held public authority and have tended to follow a special doctrine or political teaching right to its ultimate conclusion without any consideration whatsoever about public reaction or the opinions of people who have to live with such a system.

Therefore, I think Citizen Surveys, letters to the editor and so on—provided they express genuinely held opinions and not something drummed up in order to impress people—can be very valuable to government and the people who run businesses, public services and so on.

Q.: Should censorship be allowed and, if so, who should impose such censorship?

A.: As I said before, the fact that this particular newspaper is financed by the Tongan government, supported by the Tongan government, and printed on a Tongan government press, makes it different from most newspapers abroad. Because it holds this special position, I imagine that government officials, Ministers and people like that are very often nervous about the fact that some of the material in The Chronicle may be interpreted to mean that the Tongan government itself thinks this or that, or it has special attitudes about questions, whereas the Tongan government may not have such attitudes.

It could lead to misunderstandings of various types. I think so far as this is the thought behind wishing to suppress the information or slant particular news items, there is some truth in this.

If it is a question of suppressing things because they are just awkward, like public blunders, maladministration or something like that—which people have a right to know aboutt—hen I think suppression or slanting of news is a bad thing.

It means, then, that the newspaper is failing in its duty of providing information for the public, which was the whole object of having a newspaper at all.

Q.: What are your attitudes towards a private newspaper in Tonga?

A.: We have had private newspapers before. I would say that for financial reasons, private newspapers in the past have tended to be much worse equipped than The Chronicle in the way of staff, printing establishment, reporters, photographers, and so on. Therefore, private newspapers in the past have tended to be perhaps over-sensational because government sources weren’t always open to them as they are—or should be—to The Chronicle.

They have tended in the past to make wild statements because they don’t quite understand why things happen. If they have erred in the past, they have erred on the side of irresponsibility. But, then again, it started probably because the people who have run private newspapers in the past have not had any proper journalistic training. They have been people who really were trained for something else, and took this on as a side line. I think people that have been trained on responsible public newspapers would have a very large sense of responsibility. And now, if it can be properly financed, I have no objection to a private newspaper. But, because of financial reasons, private newspapers in the past have tended to observe standards well below that of The Chronicle.

I think The Chronicle has raised the standard of newspaper publication in Tonga well above anything that has been achieved before.

I think, myself, that if The Chronicle could be made into a free and responsible organ of public opinion, this would be the most desirable development, rather than starting a complete newspaper from scratch.

We’ve seen some of these newspapers in the Pacific—in Samoa and other places—where they have started up on a shoestring. The experience in other, much larger countries is that newspapers which don’t have proper financial backing are often in danger of selling their souls to the highest bidder. And it is always a big temptation to such organizations to say things only because people pay them to say it, not because they think, really, that some things are important, or the point of view is the strict truth. They open themselves up to easy corruptibility.

From my point of view, I think The Chronicle, because it can be supported by the Tongan Government, should be less corruptible. And I think that, itself, is a good thing for public information.

Q.: Would not the development in recent years of inexpensive printing methods offer greater financial security for a private newspaper than in previous times?

A.: Actually, if we could use offset or other means of printing The Chronicle other than using the government presses, this would be a very good step. I think The Chronicle should have its own press which would be devoted entirely to printing The Chronicle and would not get mixed up with the government printery.

I think a newspaper should control its own press. With any newspaper in the world, you would expect the editorial staff to control the presses.

That’s the equivalent to a captain on a ship: he tells the engineer when to start the motor, when to stop it, when to reverse, and when to go forward. I think the situation in Tonga is that the engineer tells the captain where to go. And I think this is wrong.

Q.: How do you regard recent Parliament criticisms of the newspaper?

A.: This is one of the things that one has to understand about Tonga. Tonga is a very small country, and the opinions that people have of themselves are dependent on the opinions others have of them. I think people in Tonga tend to be oversensitive to criticism.

Instead of examining the substance in criticism and trying to profit from it, if that is possible, they think that criticism is a personal affront. I think this is quite the wrong attitude. I think we can all profit from criticism.

Where you are dealing with human affairs and things that affect the lives of people, you must expect people to react differently, because they are individuals. But I think that it is the duty·of public officials to see what substance there is in criticism and to do what is right in accordance with their public duty.

Q.: How do you see the evolution of the newspaper as it exists now to a more independent, possibly private, status?

A.: Possibly, if the body that may control its policies—if such a body should be set up representative of the people of Tonga—they should make it their business to see that news is responsibly reported. If something is proposed to be suppressed, then they should carefully examine the motives for that, bearing in mind that the newspaper’s duty is to give information to the public on things that interest the public and affect them personally. If anything is to be suppressed, this body of people alone should be charged with the responsibility for saying when something should be suppressed, and nobody else. If anybody has information they think should be suppressed, then this one body alone should make the decision.

But I think it should only make such decisions after considering all the facts.

Q.: How would such a body be formed so as to assure that its membership included persons with an understanding of the functions of a newspaper?

A.: The point, of course, is not because they are journalistic experts. They are there because there should be a reasonable cross-section of people in authority in Tonga and citizens. They are the people who have to read the newspaper. The reactions you would expect of people in Tonga are quite different from reactions you would get elsewhere.

For historical and social reasons, people in Tonga are what they are because of circumstance in the way of their past history. I think their feelings should be adequately represented in a committee of some kind.

Owing to historical circumstance in Tonga—the fact that there has never been a responsible public press here—this question of absolute freedom of the press should be the ultimate aim. But we should progress towards it in stages that we can handle, rather than do it overnight. That is revolution, rather than evolution. I believe in evolution.

EPILOGUE

The interview with King Tupou IV was one of two visits to the palace. The other was just before the end of my Peace Corps tenure when I hand-delivered a “White Paper” summarizing my experiences and raising concerns about the newspaper’s future.

As I approached one of the palace helpers to hand over the paper, His Majesty’s dog—a big St. Bernard, if I recall correctly—lunged at me and took a bite of my knee.

Mindful of royal etiquette, I retreated from the palace grounds without complaint before examining the huge gash from the Royal Dog.